The Seven Ravens

Stories of brothers and sisters abound in world literature, and I particularly like tales where the girl saves the day. In the delicious compendium of folkloric motifs known as the Aarne-Thompson Index, these narratives are classified as Type 450, the Brother and Sister Tale. The most famous example is “Hansel and Gretel,” where the girl — employing both cunning and strength — rescues her younger brother from being eaten by a ravenous witch. “The Seven Ravens,” by the Brothers Grimm, is an even more adventurous story.

It begins with a wish. The parents of seven sons long for a daughter, and, voila, she is born. The sons go to fetch water, but the bucket falls into the well, and the stupefied boys do not know what to do. Their impatient father, back home waiting to baptize the girl, exclaims, “I wish the boys would turn into ravens!” And they do.

The parents are sad, but the Grimms tell us they are “somewhat consoled” by their beautiful daughter. (Note the “somewhat”; in fairy tales, there is often a quality of almost-but-not-quitethat quietly shapes both the mood and the plot of a story.) The parents never tell the girl that she has brothers, now ravens. And then one day, because familial trauma is hard to erase, she overhears people talking about the boys and how she is to blame for their fate. Her parents declare that she’s innocent, but she’s heartbroken. She decides she must rescue her lost raven brothers.

And so the girl sets forth on one of the greatest solo search-and-rescue missions in literature. She carries a ring, a jug of water, and a chair to sit upon when she gets tired. A chair! Now that’s planning. I wonder, was it a wooden chair, and did she tie it to her back? Was it heavy or unwieldly? This sort of everyday logic is omitted in fairy tales. To turn boys into ravens requires merely a poof.

My brother, Andy Bernheimer, and his collaborators at Bernheimer Architecture, chose this story because they felt great affection for its resourceful heroine. She is so intrepid! The Grimm Brothers write, “She came to the sun, but it was too hot and terrible, and ate little children. She hurried away, and ran to the moon, but it was much too cold, and also frightening and wicked, and when it saw the child, it said, ‘I smell, smell human flesh.’”

Onward she trucks, until eventually she meets up with the morning star, who gives the girl a bone and tells her it will open the glass mountain where her brothers are kept. Though she carefully wraps up the bone in a kerchief, it’s lost, and so she neatly cuts off a finger to use as a key. It works! The glass mountain opens for her. (Donald Barthelme’s “The Glass Mountain” picks up on this compelling motif from old fairy tales in his iconically postmodern, phallic, and vertical story.)

The girl drops the ring into a little cup at a table, exchanges words with a dwarf, and then hides behind a door, as her brothers, the ravens, come in to enjoy their small suppers. I love that there is no explanation for why she must hide, or why one brother must discover the ring in his cup, in order that the ravens may be turned back into boys. I also love how they all return happily home — to the father who caused their transformation, and to the mother who conspired to keep their existence a secret, driving the girl to self-amputation.

Most of all, I love that this story, with its themes of loyalty and restoration, appealed to my brother’s firm. It’s a terrific adventure story that more readers should know. Bernheimer Architecture’s design highlights the physical landmarks along the female foot soldier’s walk to the end of the earth, a walk of protest and heart.

— Kate Bernheimer

Curated by

Kate Bernheimer and Andrew BernheimerPublished in

Places Journal

The Metamorphosis

The Flight

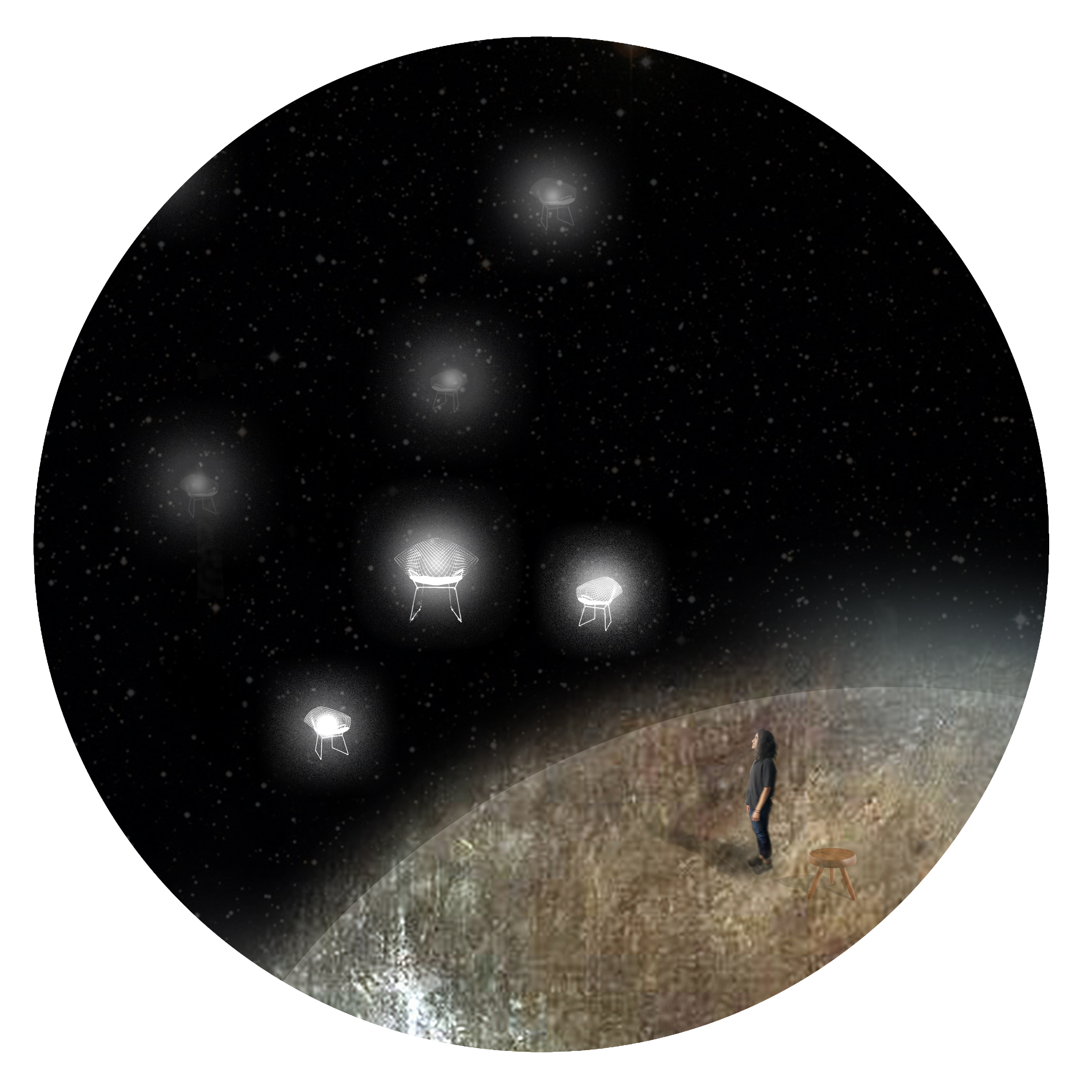

This is the sixteenth installment of our Fairy Tale Architecture series, and the sixth that your firm has designed. I know that one of your goals in selecting this tale was to avoid the kind of story I’ve assigned to you in the past (often featuring a child who perishes). You noted in an earlier interview that you do not aspire as an architect to create spaces of punishment and suffering. Is this now a utopian image? What is the interplay of darkness and light in the universe depicted here?

Yes, we had grown a bit weary of dead kids, of mutilations (though this story has one, albeit self-inflicted and purposeful). So this tale was intriguing in that it was about heroism, a saving. We felt particularly drawn to the heroine, a strong young female, who courageously moves in and out of darkness to find her seven brothers — especially in light of the current political climate and the issues of gendered power it has highlighted.

We wanted to draw this story, which describes many events in several scales, in simultaneity. The drawings had to collapse multiple episodes into a kind of event-space that willfully distorted time and space. Architects typically draw “at scale,” and we wanted to develop a mechanism to alter that sense of scale.

In our composition, we are displaying the physical and mental emotions inherent to the heroine’s quest through light and dark, saturation and solitude. Scale isn’t just the space and objects within space. It can also be scale of emotion: loneliness, togetherness, despair and perseverance.

Would you like to see a glass mountain built in real life, and where? Would it be possible? The image brings to mind global warming. If all the glaciers melt, would they be depicted, in thousands of years, by giant commissioned memorials — glass sculptures? Do you think you would apply to be the architect for something like that?

That’s a vision of a dystopia that we, as optimistic architects looking to improve people’s lives, need to confront and do all we can to avoid as a reality. It would be disheartening to have that (admittedly amazing) commission.

You name artists, designers, and architects like Brueghel, Harry Bertoia, Eero Saarinen, and Hilla and Bernd Becher as among the aesthetic inspirations for this design. That’s a great list. Can you point to one work and describe how it operates here?

Similar to a Homeric epic covering vast expanses of time and space, “The Seven Ravens” tells the tale of a galactic journey composed of moments, places, and people across many scales. Thus the inclusion of snippets of other artwork; it is a collage of decontextualized works which collectively make a new story scaled to the Grimms’ original.

Bertoia chairs are used in the design to depict stars, because they are beautiful and ethereal (like stars) but one cannot comfortably sit on them. Unless, of course, one is a gaseous celestial body.

Scale isn’t just the space and objects within space. It can also be scale of emotion: loneliness, togetherness, despair and perseverance.

The Picnic

The Sun

The Stars

The Glass Mountain

The Ravens’ Dinner

Related Research