The Boy Who Went Forth To Learn Fear

This is an incredible story few seem to know. It has circulated in fairy-tale books with different titles: “The Boy Who Wanted to Get the Shivers,” “The Little Boy Who Wanted to Know What Trembling Was,” “A Youth Who Went Forth to Learn about Fear,” “The Youth Who Wanted to Shudder,” “The Boy Who Wanted the Willies.”

In the version that led me to assign this tale to my brother, the story opens with the hero walking in the woods with his sister one night. She’s terrified, but he feels nothing. And then one day, the story tells us: he goes out into the world to learn about this mysterious thing known as fear.

Nothing does it for him. Not the priest who pretends to be a ghost in a tower: the boy pushes him down the deep stairwell to a very bad death, irritated that “the ghost” will not speak. Not the seven hanged men — dead — whom the boy props up and warms by a fire. Heated, they come back alive and burst into flames, but he is merely annoyed by their conflagration. He hangs them again.

The boy is cheerfully destructive. At one point two black cats — described in some versions as larger than the boy — pay him a visit:

They said: ‘Friend, shall we have a game of cards?’ ‘Why not?’ he replied, ‘but just show me your paws.’ Then they stretched out their claws. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘what long nails you have! Wait, I must first cut them for you.’ Then he seized them by the throats, put them on the cutting-board and screwed their feet fast. ‘I have looked at your claws,’ he said, ‘and my fancy for card-playing has gone,’ and he struck them dead and threw them out into the fish-pond.

The insanity of this strange pilgrimage is hard to resist. One night the boy sleeps in a haunted bed; it drags him around with the force of six horses and contorts itself around his body, but he feels basically nothing. Dismembered characters enter his room, their torsos topped by talkative heads. No big deal. But we readers are enthralled, for this is all rendered in the flat, abstract, depthless technique of the Brothers Grimm — those underrated, meticulous stylists. “If only I could get the shivers, if only I could get the shivers,” the boy laments.

Finally, he is dunked into a barrel of minnows; and so it is that he feels what fear feels like. The fairy tale gives him the real sensation of fear, not a representation, of it. The tale is concrete.

The architecture of this particular story also resides in its “almost there, not yet there” quality. The boy’s journey could go on endlessly, and indeed it has, in various retellings and interpretations over the centuries. The world terrifies, the tale enchants.

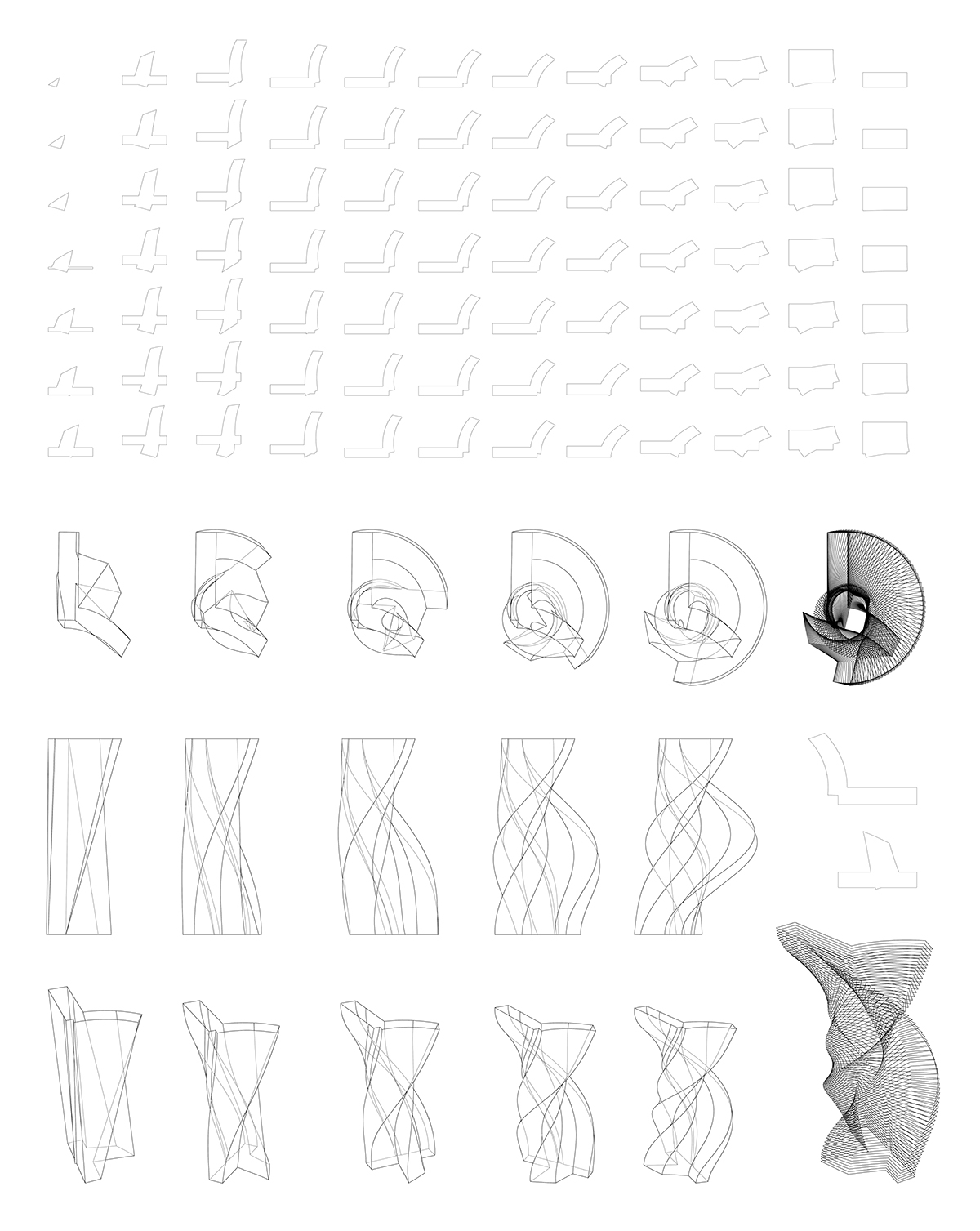

Bernheimer Architecture enters the story via a site-specific moment in a 20th-century war — once upon a time in Nazi Germany. In this gallery, they have re-imagined the boy as a German soldier stationed at the Edersee Dam in May 1943, when it was destroyed by the British Royal Air Force. The architects diagrammed the site’s topography, the weaponry (a “bouncing bomb”) and the space created by the cataclysm; then they fabricated models from their drawings. The boy who set forth to learn what fear was experiences the fury of the bombing: a violent and necessary disruption of inhabited space.

In a letter earlier this year, my brother described the cerebral process by which he and Vera Leung were coming up with this design: they studied the story as rendered poetically by the Brothers Grimm; they set it aside and visited the history of the Edersee Dam bombing; and then they compressed both narratives into what he called a “mindscape.” The soldier would stand on the dam at the time of the bombing, but also inside the Grimm story.

All this reminds me of the poetics and sensation of Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “Casabianca,” which begins:

Love’s the boy stood on the burning deck

trying to recite ‘The boy stood on

the burning deck.’ Love’s the son

stood stammering elocution

while the poor ship in flames went down.

Bishop’s poem creates a new mindscape of a 19th century poem, “Casabianca,” by Felicia Hemans:

The boy stood on the burning deck

Whence all but he had fled;

The flame that lit the battle’s wreck

Shone round him o’er the dead.

Yet beautiful and bright he stood,

As born to rule the storm;

A creature of heroic blood,

A proud, though child-like form.

So, too, does the Grimm fairy tale reverberate through history, turning back on itself in a vortex.

We have much to learn about fear. We cannot know it, but we can feel it. And if we can feel it, we will better know what to fear.

— Kate Bernheimer

Curated by

Kate Bernheimer and Andrew BernheimerPublished in

Places Journal

Bouncing Bomb

Rotational Diagrams

At the end of “The Boy Who Set Forth to Learn About Fear” a boy finally learns what fear is when he is dunked into a barrel of fish; even skinned corpses can’t teach him to feel the affect of terror. It’s a great story, isn’t it?

That’s a leading question! Yes, it’s a great story, though perhaps more opaque than we had hoped. Also, it is more humorous, in a very odd way, than we expect stories that have violent content like this to be.

In your model and in your rendered drawings, the story resides within dark planes of destruction and fear. Story is abstracted from hero. Are these the designs of a witness, or are they made by the architect of the attack?

These shapes were conceived of as the representation of an imagined experience of the space of an explosion during the dam bombing, ergo the space of the soldier, the witness, the individual who perhaps has no anticipation of what is coming but then, in a whirlwind, experiences the space of violence. And, perhaps, if our soldier was conscious long enough, fear.

Italo Calvino mentions, in his introduction to the brilliant Italian Folktales, that it is the “firm form” of fairy tales that magnetizes him to these strange, primal stories. You have described one of your objectives in this project as finding pure form — can you say more about that?

I want to be sure that this doesn’t sound like I ever claimed that I could discover anything like an actual “pure form”; this is a fool’s presumption and the territory of egotists. But in the terms of the story, we wanted to distill experience to a shape, a volume, instead of a literal space-type (“castle” or “gingerbread house,” etc.). We were struggling with a literal space, so we had to reduce the story and purify the objective.

So the idea of “form” exists here on at least two levels — first in the “form” of the story, the technical structure of the narrative (which wasn’t so interesting to us, and also frankly confusing), and second in the spaces of the strange experiences of the boy who goes forth. These spaces of his experience (the twisting and turning bed was an especially curious one) were where the investigation began, sometimes with a bit of literality that was too easy.

We also chose this path in part because the structure of the story wasn’t accessible, the events were scattered, random and untethered to a place. So we had to find the rope, make the place, invent a story-space outside the tale itself.

You were always afraid of bees when we were kids. What are you most scared of now?

Being stuck next to a shirtless accordionist in an overcrowded F train during a late August heat wave.

These shapes were conceived of as the representation of an imagined experience of the space of an explosion during the dam bombing.

The Explosion

Ceramic 3D Print of the Explosion Space

Print Detail

Related Research